A cash flow statement is one of the most critical financial reports for any small business. It shows exactly how much cash is entering and leaving your company during a specific period—whether that’s a month, quarter, or year. Alongside the balance sheet and income statement, it forms the foundation of smart financial management. Together, these three reports help you understand not just profitability, but also whether you truly have enough cash available to keep your business operating smoothly.

For U.S. small businesses, this is more than just paperwork. Cash flow statements are often required under financial reporting standards and are essential for lenders, investors, and even tax compliance.

Here’s the key difference: while your balance sheet shows what you own (assets) and what you owe (liabilities) at a single point in time, a cash flow statement tracks the actual inflows and outflows of money over a period. In other words, it tells you the truth about how much cash you really have available—not just what’s owed to you on paper.

At Rocket Bookkeeper, we help U.S. small business owners use cash flow statements as powerful tools for decision-making, growth planning, and financial stability. In this guide, we’ll take a closer look at what a cash flow statement does, why it’s so important, and walk you through a real-world example—plus provide a template you can use to create your own.

What Is the Purpose of a Cash Flow Statement?

A cash flow statement serves a simple but powerful purpose: it shows you how much cash your business actually has on hand during a specific period—whether that’s monthly, quarterly, or annually.

While your income statement does a great job of showing revenues and expenses, it doesn’t reveal your true liquidity. In other words, an income statement can tell you if your business is profitable, but it doesn’t guarantee that you currently have enough cash to cover payroll, rent, or supplier payments.

This is where the cash flow statement becomes essential. It bridges the gap between profits on paper and real cash availability, helping small business owners in the U.S. make smarter financial decisions every day. At Rocket Bookkeeper, we emphasize cash flow management because it’s the key to keeping your business running smoothly and preparing for growth.

Cash Flow Statement vs. Balance Sheet

A balance sheet provides a snapshot of your business’s financial position at a specific point in time—usually at the end of a month, quarter, or year. It lists what your business owns (assets), what it owes (liabilities), and the remaining value (owner’s equity).

However, what a balance sheet doesn’t reveal is your cash activity—the inflows and outflows of money that directly affect your company’s day-to-day health. That critical information lives in the cash flow statement, which tracks how much cash is actually moving through your business during a period.

At Rocket Bookkeeper, we help small business owners in the U.S. use both reports together: the balance sheet for a static view of financial standing, and the cash flow statement for a dynamic view of real liquidity.

Cash Flow Statement vs. Income Statement

Relying only on an income statement to track your business’s financial health can be misleading—and sometimes dangerous. Here’s why.

If you use accrual accounting, your income and expenses are recorded when they’re earned or incurred, not when the cash actually moves in or out of your bank account. By contrast, the cash accounting method records money only when it’s received or paid. (👉 See our guide on cash vs. accrual accounting to learn more.)

This means that even if your income statement shows a strong profit, you may not actually have that cash available to spend. That’s where the cash flow statement comes in. It adjusts the information from your income statement to show your net cash flow—the real amount of money you can use right now.

For example, depreciation appears as a monthly expense on your income statement. But in reality, you already paid for that asset upfront, and no new cash is leaving your account each month. The cash flow statement reverses that adjustment, giving you a true picture of your available cash instead of just theoretical expenses.

At Rocket Bookkeeper, we help U.S. small businesses go beyond profit numbers and understand the actual liquidity they have on hand—so they can make smarter decisions about payroll, growth, and investments.

Why Do You Need a Cash Flow Statement?

If your business uses accrual accounting, a cash flow statement is not just helpful—it’s essential for accurate financial analysis. Here’s why every U.S. small business should maintain one:

- It Shows Your Liquidity

A cash flow statement tells you exactly how much cash you have available for operations at any given time. This clarity helps you decide what you can afford—such as payroll, rent, or new equipment—and what might need to wait. - It Tracks Changes in Your Finances

Unlike other reports, the cash flow statement reflects how assets, liabilities, and equity are changing through actual cash inflows and outflows. Together, these categories form the backbone of your accounting system and give you a more accurate measure of business performance. - It Helps You Forecast the Future

By analyzing past and current cash flow statements, you can project future cash availability. These cash flow projections are critical for planning long-term strategies, preparing for expenses, and avoiding liquidity crises. - It Strengthens Loan & Funding Applications

If you’re applying for a business loan, line of credit, or investor funding, lenders will expect to see current cash flow statements. Having accurate, up-to-date reports makes your business more credible and trustworthy.

At Rocket Bookkeeper, we help small businesses not only prepare cash flow statements but also use them as a strategic tool—for growth planning, financial stability, and securing funding.

Negative Cash Flow vs. Positive Cash Flow

When your cash flow statement shows a negative number at the bottom, it means you spent more cash than you received during that period—this is known as negative cash flow. While it may sound alarming, it’s not always a bad sign. For example, early-stage startups often operate with negative cash flow as they invest heavily in growth, track their burn rate, and work toward profitability.

On the other hand, a positive cash flow occurs when your business generates more cash than it spends during the period. This generally means you have more liquidity to cover expenses or reinvest in growth. But positive cash flow isn’t automatically good news. For instance, if your cash flow increased because of a large loan, it may improve liquidity temporarily but add long-term debt.

👉 In short: both positive and negative cash flow require context. The numbers alone don’t tell the whole story—you need to look at the bigger financial picture.

Where Do Cash Flow Statements Come From?

Cash flow statements are typically prepared using information from your income statement and balance sheet. If you manage your own books, you can calculate them monthly using spreadsheets like Excel or Google Sheets. Many accounting software platforms can also generate cash flow statements automatically, based on the data you enter into your general ledger.

However, there’s an important catch: your cash flow statement is only as accurate as your bookkeeping records. If your books aren’t up to date or transactions are recorded incorrectly, your cash flow statement will give you misleading results.

That’s why many small business owners turn to professionals like Rocket Bookkeeper. We ensure every transaction is recorded properly so your cash flow statement always reflects the true health of your business—helping you make confident financial decisions.

Direct vs. Indirect Methods of Preparing a Cash Flow Statement

When it comes to preparing a cash flow statement, businesses can take two approaches: the direct method or the indirect method. Both are approved under U.S. GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles), but the indirect method is most commonly used by small businesses in the U.S.

The Direct Method

With the direct method, you record every cash transaction as it happens—tracking all inflows (like customer payments) and outflows (such as rent, utilities, and payroll). At the end of the reporting period, those records are summarized into your cash flow statement.

While this method gives a very clear view of cash movement, it requires meticulous record-keeping. Every receipt and payment must be tracked and categorized, making it more time-consuming and labor-intensive. Even when businesses use the direct method, they still need to reconcile their results with the indirect method for accuracy.

The Indirect Method

The indirect method starts with your net income (from the income statement) and adjusts it to reflect actual cash flow. This involves reversing non-cash expenses (such as depreciation) and accounting for changes in working capital (like accounts receivable, inventory, and accounts payable).

Because it is simpler and faster, the indirect method is the preferred choice for most U.S. small businesses. It avoids the need to track every single transaction individually and doesn’t require reconciliation with the direct method.

How the Cash Flow Statement Works with Other Reports

Your cash flow statement doesn’t exist in isolation. It relies on information from your income statement and balance sheet:

- The income statement shows how money entered and left your business during a period.

- The balance sheet shows how those transactions impacted assets, liabilities, and equity.

Put simply:

👉 Income Statement + Balance Sheet Adjustments = Cash Flow Statement

Example of a Cash Flow Statement

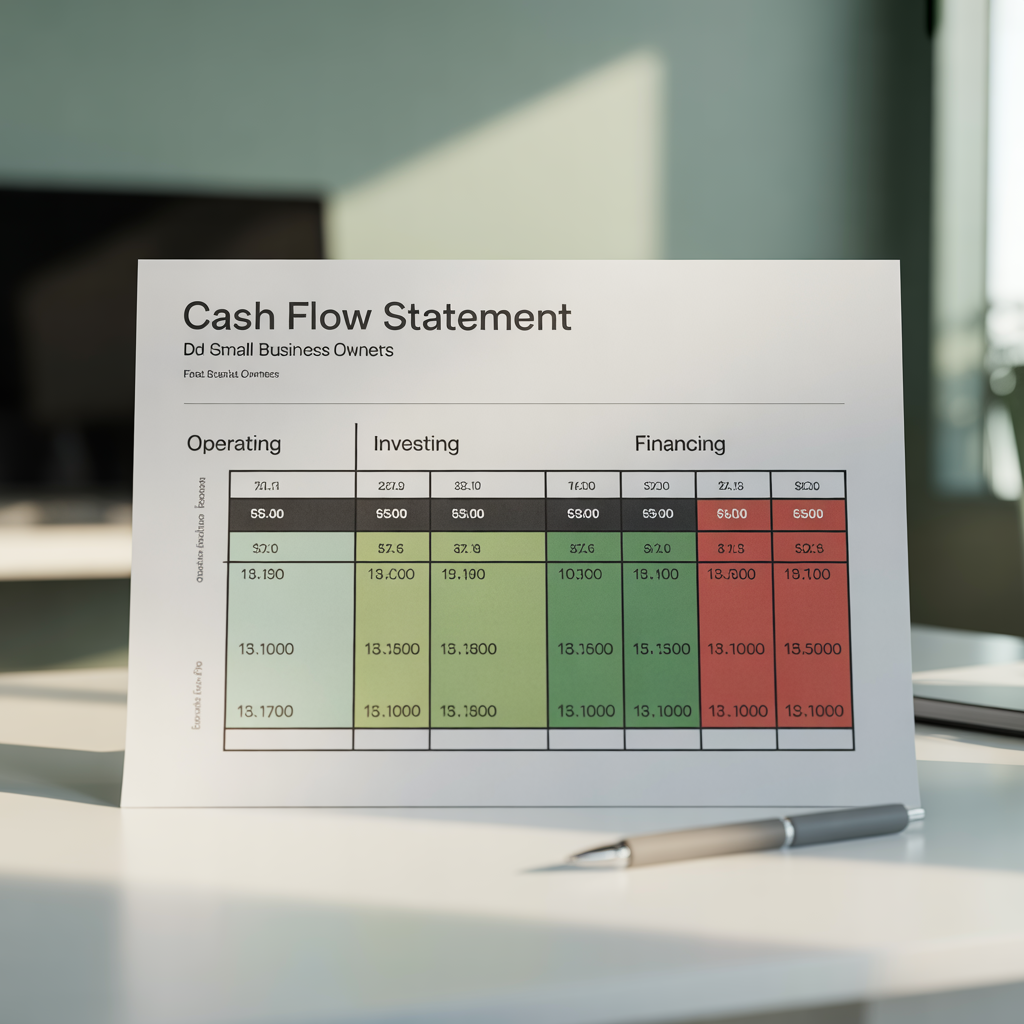

Now that you understand what a cash flow statement is and how it’s prepared, let’s look at a practical example.

In a typical cash flow statement, every entry is either an inflow (cash coming in) or an outflow (cash going out):

- Negative amounts (shown in red) represent decreases in cash. For example, if you see ($30,000) next to “Increase in Inventory,” it means your business spent $30,000 in cash to purchase more inventory—reducing your available balance.

- Positive amounts (shown in black) represent increases in cash. For example, $20,000 listed under “Depreciation” is an expense on your income statement, but because no cash actually leaves your account, that amount is added back to net income.

Every cash flow statement is divided into three sections, which together explain how money is moving through your business:

- Cash Flow from Operating Activities – Cash earned or spent through day-to-day business operations (sales, payroll, rent, utilities).

- Cash Flow from Investing Activities – Cash used for or earned from long-term investments (buying equipment, selling property).

- Cash Flow from Financing Activities – Cash received or paid out from loans, lines of credit, or owner’s equity.

👉 This breakdown helps small business owners quickly see where cash is really coming from and where it’s going—a vital insight for managing liquidity.

At Rocket Bookkeeper, we prepare cash flow statements that not only meet compliance standards but also give small businesses in the U.S. a clear picture of their financial health.

Cash Flow from Operating Activities

For most small businesses, operating activities make up the largest part of cash flow. These are the day-to-day transactions that keep your business running.

- If you own a pizza shop, operating activities include the cash you earn from selling pies and the money you spend on ingredients, payroll, and utilities.

- If you’re a massage therapist, it’s the cash earned from sessions and the money spent on rent and supplies.

Let’s break it down in a simplified example:

- Net Income – Your total earnings after expenses, reported on the income statement.

- Depreciation – A non-cash expense (e.g., $20,000). Since no actual cash left your account, it’s added back.

- Increase in Accounts Payable – Money you owe (say $10,000), but haven’t paid yet. It stays in your account for now, so it’s added back.

- Increase in Accounts Receivable – Money billed to clients but not collected yet (e.g., $20,000). Since you don’t have the cash, it’s deducted.

- Increase in Inventory – Purchasing stock (e.g., $30,000) reduces cash on hand, so it’s deducted.

After adjustments, the net cash from operating activities is $40,000—even though the income statement showed $60,000 in profit. This highlights why the cash flow statement gives a more realistic view of liquidity.

Cash Flow from Investing Activities

The investing section covers money spent on or earned from long-term assets like equipment, vehicles, property, or financial products.

- Buying a $10,000 mower for your landscaping business reduces cash by $10,000, even though you now own an asset of equal value.

- Purchasing a $140,000 retail property reduces cash on hand by $140,000, even though you gained a building.

In our example:

- Purchase of Equipment → $5,000 spent, recorded as a cash outflow.

For most small businesses, investing activities don’t dominate cash flow—but they’re still important for understanding working capital.

Cash Flow from Financing Activities

The financing section records money borrowed, repaid, or invested by owners.

- Outflows: Loan repayments, credit line payments, or dividends.

- Inflows: Loan proceeds, new investor contributions, or additional owner funding.

In our example:

- Notes Payable → A $7,500 loan received, added as cash inflow.

Total Cash Flow for the Month

At the bottom of the statement, you see your net cash flow.

- Example: The income statement reported $60,000 net income, but after adjustments, the cash flow statement shows $42,500.

- That $42,500 is the real amount of cash available to spend today.

Without a cash flow statement, you might assume you have $60,000 and overspend, misbudget, or misrepresent your liquidity to lenders.

Using a Cash Flow Statement Template

If you’re handling your own bookkeeping in Excel or Google Sheets, a cash flow statement template can save time and reduce errors.

👉 Rocket Bookkeeper’s Free Cash Flow Statement Template is designed for U.S. small business owners. It’s simple to use and helps you track operating, investing, and financing activities clearly—so you always know how much cash is available.

At Rocket Bookkeeper, we can also manage this process for you. From monthly bookkeeping to cash flow management, we make sure your numbers are accurate and ready for growth or funding applications.

How to Track Cash Flow Using the Indirect Method

Most U.S. small businesses prefer the indirect method of preparing a cash flow statement because it’s simple, efficient, and doesn’t require tracking every single transaction in real time. Instead, you start with net income from your income statement and then adjust it to reflect actual cash activity.

Here are the four golden rules to remember:

- Increase in Assets → Decrease in Cash Flow

(Example: Buying more inventory reduces your available cash.) - Decrease in Assets → Increase in Cash Flow

(Example: Collecting receivables adds more cash to your account.) - Increase in Liabilities → Increase in Cash Flow

(Example: Delaying supplier payments temporarily boosts cash on hand.) - Decrease in Liabilities → Decrease in Cash Flow

(Example: Paying off a loan reduces your cash balance.)

By applying these adjustments, you turn the income statement’s profit figure into a realistic picture of your cash position.

👉 If you already understand the basics, you can start experimenting with Rocket Bookkeeper’s free financial templates:

- Income Statement Template

- Balance Sheet Template

- Cash Flow Statement Template

These tools make it easier to prepare your own reports and track liquidity month by month. But if you’d prefer expert help, Rocket Bookkeeper can manage your cash flow reporting for you—ensuring accuracy, compliance, and insights you can use to grow your business.

Creating a Cash Flow Statement from Your Income Statement and Balance Sheet

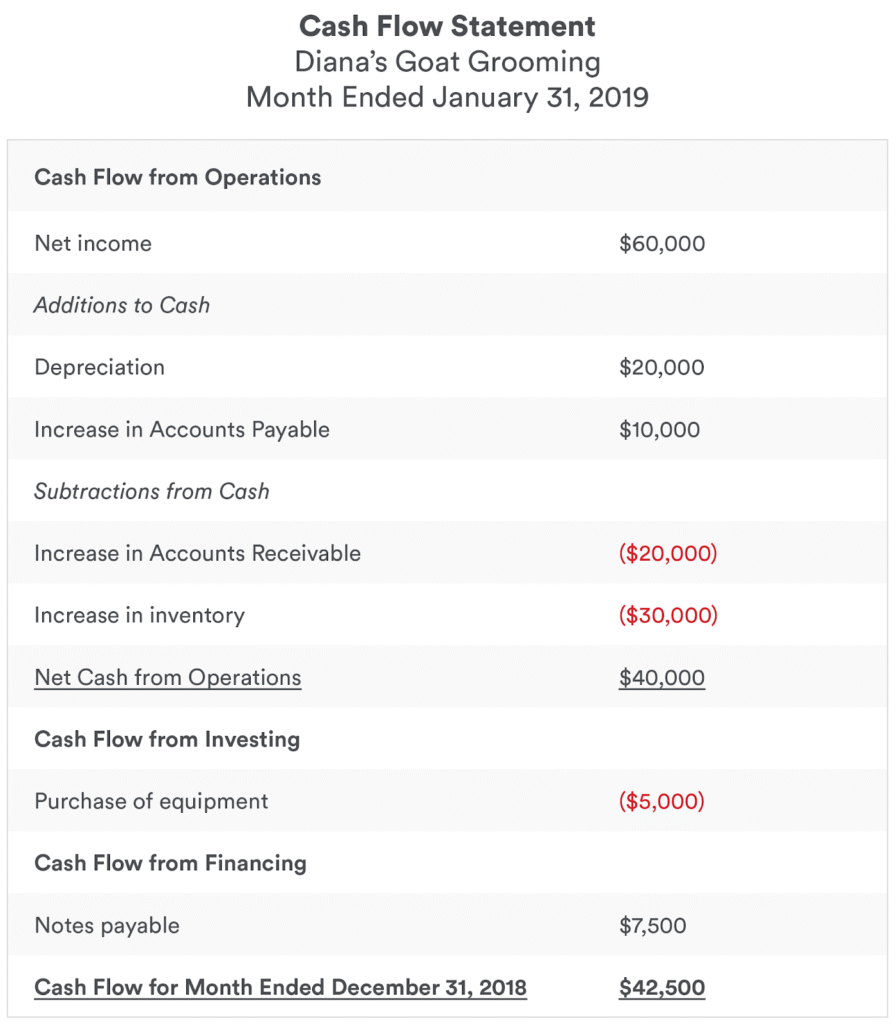

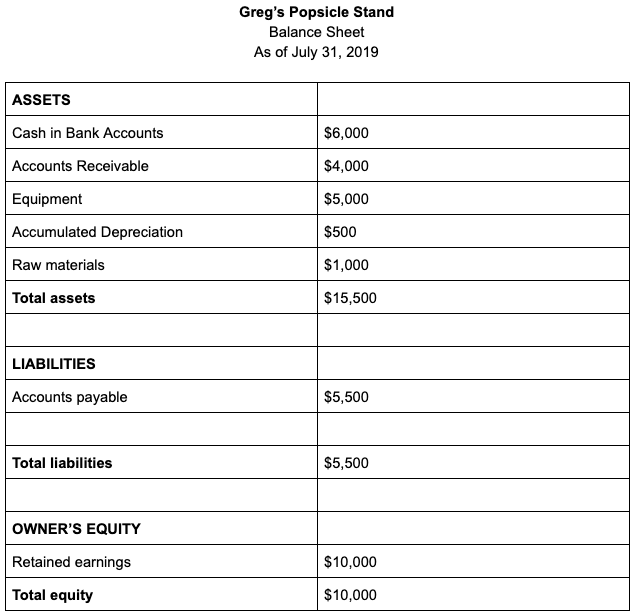

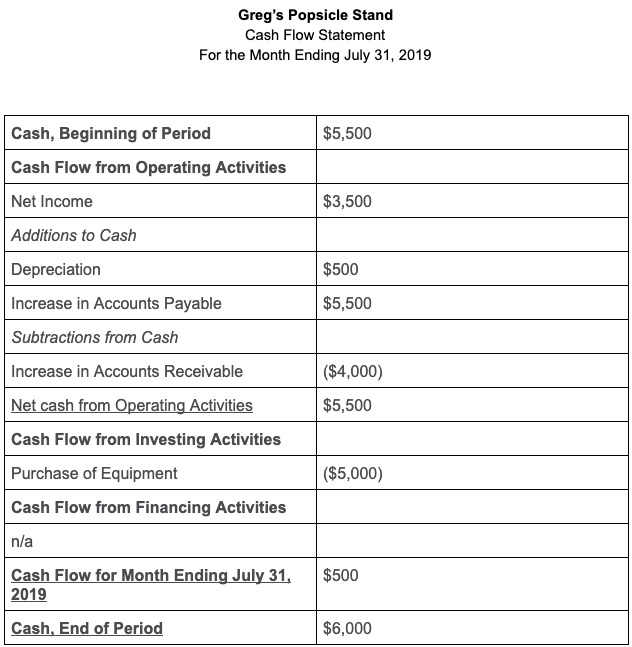

To see how everything comes together, let’s walk through a simple example of preparing a cash flow statement—using Greg’s Popsicle Stand for July 2019.

Creating a cash flow statement from your income statement and balance sheet

Let’s say we’re creating a cash flow statement for Greg’s Popsicle Stand for July 2019.

Our income statement looks like this:

Note: For the sake of simplicity, this example omits income tax.

And our balance sheet looks like this:

Remember the four rules for converting information from an income statement to a cash flow statement? Let’s use them to create our cash flow statement.

Our net income for the month on the income statement is $3,500 — that stays the same, since it’s a total amount, not a specific account.

Additions to Cash

- Depreciation is included in expenses for the month, but it didn’t actually impact cash, so we add that back to cash.

- Accounts payable increased by $5,500. That’s a liability on the balance sheet, but the cash wasn’t actually paid out for those expenses, so we add them back to cash as well.

Decreases to Cash

- Accounts receivable increased by $4,000. That’s an asset recorded on the balance sheet, but we didn’t actually receive the cash, so we remove it from cash on hand.

Our net cash flow from operating activities adds up to $5,500.

Step 1: Start with Net Income

From the income statement, Greg’s business earned $3,500 in net income for the month. This number becomes the starting point of the cash flow statement.

Step 2: Add Back Non-Cash Expenses

- Depreciation: Although depreciation is recorded as an expense on the income statement, no cash actually leaves the business. Let’s say $1,500 was recorded as depreciation. We add this back to net income.

Step 3: Adjust for Changes in Liabilities

- Accounts Payable: The balance sheet shows an increase of $5,500 in accounts payable. This means Greg owes suppliers more money, but hasn’t paid them yet—so that cash is still in hand. We add $5,500 to the cash flow statement.

Step 4: Adjust for Changes in Assets

- Accounts Receivable: The balance sheet also shows an increase of $4,000 in accounts receivable. This means Greg billed customers but hasn’t collected the cash yet. Since it’s not available to spend, we subtract $4,000 from the cash flow statement.

Step 5: Calculate Net Cash Flow

After these adjustments, Greg’s net cash flow from operating activities comes out to $5,500—even though his net income was only $3,500.

👉 This example shows why cash flow statements are so valuable. They bridge the gap between accounting profits and actual cash available, giving business owners a more accurate picture of financial health.

At Rocket Bookkeeper, we help U.S. small business owners create cash flow statements like this every month—so you always know exactly where your money stands.